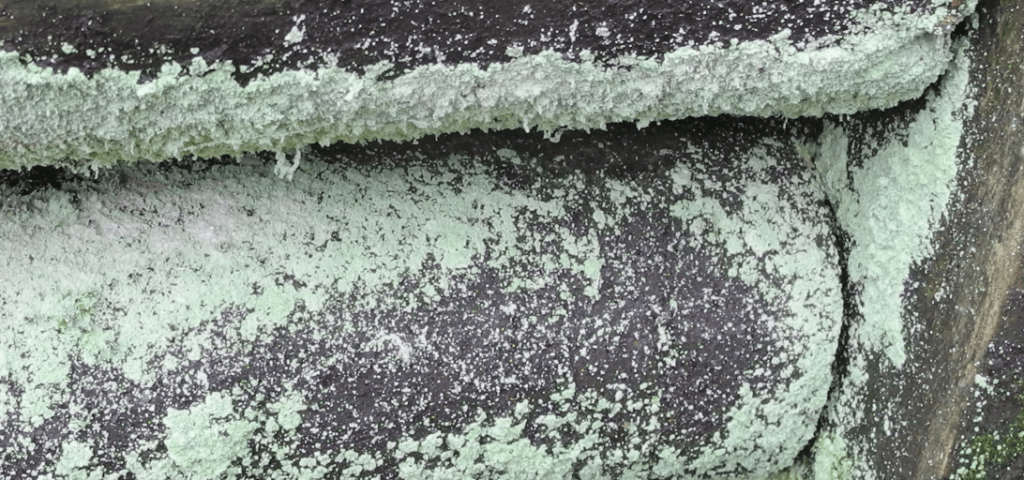

Look at the dog lichen in the frost.

Dog lichen with frost and Dog lichen with fruiting bodies

On the underside of a dog lichen there are white root-like structures. They are supposed to resemble the teeth of a dog. Although, the orange-red fruiting bodies, in my view, are more indicative as they look like blood dripping from fangs. It was due to having associations with dogs that, historically, these lichens were considered as a cure for rabies. Nowadays, they are indicative of wet places.

There are many different lichens, growing on almost any surface, including trees, rocks, soil, and artificial surfaces such as concrete and tarmac.

At this time of year, they are more noticeable because there are no leaves on the trees.

Lichens are a partnership between a fungus and one or two types of algae.

The fungus gives the lichen structure providing a layer around the algae protecting it from extremes of temperature and drought.

In return, algae through photosynthesis provides carbohydrate nutrition for both partners.

There are three distinctive types of Lichen

Crustose lichens are the first type to consider, and their name comes from their crust-like appearance on a surface. They are too hard to dislodge, even when scratching them with a fingernail.

Crusty lichen on a fence

The second type is the leafy lichens, often referred to as Foliose lichens, and unlike the group above, you can lift them off their surface with the scratch of a fingernail.

A leafy lichen on bark

Finally, the third type is the Fruticose lichens. Bushy in appearance, these lichens are usually only attached by one sucker-like hold fast.

Bushy lichen on a twig

Lichens are highly sensitive to air quality, and as a result, they are good indicators of air pollution.

In the past, sulphur dioxide affected air quality, and because of this, very few lichens could survive, but as air quality improved, lichens started to reappear.

The rule was the fluffier the lichen, the cleaner the air.

It will be interesting to see if, in the future, increasing levels of nitrogen from car use and farming will have a detrimental impact on lichens as not all lichens can tolerate high levels of this type of pollution.